Age Of the Electron Part IV: The ElectroDollar, a Possible Answer to the Fraying US Global Currency Reserve System

What do China, Bitcoin, Renewables, and the US Petro-Industrial Complex have to do with each other?

America has an energy problem. The established petro-industrial order is unwinding, and US global hegemony with it. As it unwinds, a new paradigm is emerging — the Age of the Electron. In much the same way US economic and military hegemony, the USD reserve system, and the petro-industrial complex emerged out of access to cheap oil post World War II, The Age of the Electron will bring with it its own emergent institutions. While some existing institutions may be able to absorb the gradual emergence of new ideas in general, this paradigm shift is a step-change jump and it is unlikely that our existing institutions will adapt. There will be far reaching consequences for global power structures and economic systems, the currencies we use, the energy we consume, and the technologies that consume it.

Given that, we must not depend on preparing our existing institutions for these radical changes. Rather, we must build new ones. In order for the US to thrive in the 21st century, we must move away from the “efficiency” of globalization cemented in the 1990's and instead focus on the resilience of regional, on-shored supply chains.

There are three converging phenomena that we must contend with:

The USD as a global reserve currency is now undermining the strategic goals of the US by preventing the on-shoring of crucial clean energy (and other) supply chains, while making us a victim of our own success in global energy markets.

Bitcoin as a currency is native to a digital world driven by electricity, which maps well to the Age of the Electron. Its creation produces a clearing price for what is actually a productive use of electricity, incentivizing only real GDP growth.

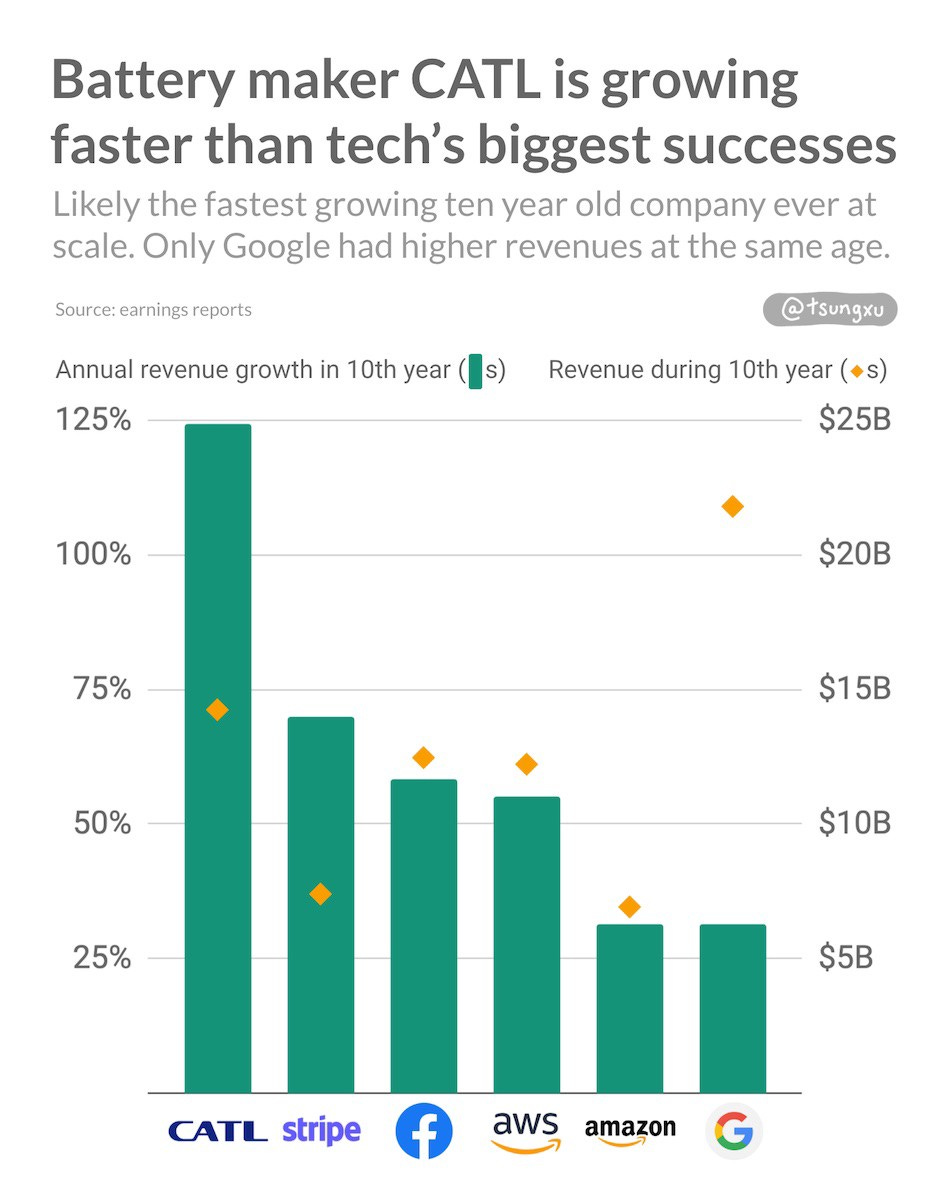

China is emerging as dominant in solar and battery supply chains, which spells trouble for our clean energy transition and US global positioning.

As electricity now fast becomes the most important commodity in the world, it makes sense to explicitly tie our money to its production, like we have done throughout human history. Energy consumption is the most important pillar of any modern economy, and our money systems have already taken note. Namely, since the 1970s the dollar has been backed by oil. And prior to the modern era, gold and silver were the most valuable commodities, and thus made sense as a backer of currency. Similarly, in the near future an electrodollar construct offers us a way out of the petrodollar system and towards institutions that can better support decarbonization efforts. It is imperative that the US begins building these new institutions and reorienting foreign and domestic policies around them.

The energy transition holds massive opportunity. In this piece, we will explore the history of the petro-industrial order and cement the argument that much of today’s domestic social ills are directly downstream of our energy problems. Leaning into decarbonization and electrification will reinvigorate domestic labor by rapidly on-shoring manufacturing while making our supply chains and global position more resilient. As Peter Zeihan writes in Disunited Nations, across almost every metric that matters — natural resources, internal trade routes, external trade routes, defensive borders, military force — the US remains dominant, despite the current precarious state of the empire. This means that our only enemy is ourselves. By doubling down on the energy transition, we can fix domestic labor issues and reduce wealth inequality, rebuild our industrial base and government balance sheets, and emerge a more resilient, unified nation.

Prelude: Patriots Say, “Death to the USD’s Global Reserve Status”

A new world monetary order is emerging that doesn’t require the USD as a reserve currency, and that’s a good thing long term (or as Zoltan Pozsar says, we are witnessing the birth of Bretton Woods III). The onset of COVID-19 in 2020 brought to a head the dynamics that had been brewing for decades in global energy and currency markets, which have now accelerated with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. This has come with it some surprising realizations, most notably that the USD’s global reserve currency status explicitly hinders our aims. More important, however, is recognizing that the US’s ability to react to these new realities with forward-thinking policies will define us for decades to come. Central to our reaction ought to be prioritizing energy policy above all others, with the understanding that manufacturing supply chains, dirt cheap energy, the rebuilding of the US working class, and the currencies we use are all deeply intertwined.

There is no better example than the current Russian invasion of Ukraine to demonstrate that the USD’s reserve status limits our ability to act, and that any action will self-inflict harm. In the days after the invasion, the US rolled out a set of sanctions that somehow still allowed Russian oil and gas (60% of Russia’s GDP) to flow into the global system, and refusing to remove Russia completely from SWIFT despite almost universal calls to do so. The only possible explanation for this is that there was concern over what this shock would do to global energy markets, and the USD with it (see more detail here). Continuing to buy their energy meant that the West was explicitly financing Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, despite being against it. And while the US eventually did agree to stop buying oil, other NATO countries (that actually need it) have not. In a different world, the US could have acted swiftly and unilaterally — imagine the West continuing to rely on exports like this from the USSR — while emerging unscathed.

Whether it’s their intention or not, the Biden Administration’s actions are accelerating the demise of the USD’s reserve status as the seizure of Russian reserves effectively ended the USD as a reliable reserve currency, while concurrently introducing inflation to the West via supply shocks to global commodities by sanctioning Russian exports. This, counterintuitively, is a good thing: as Gromen points out, we were able to send a signal to the world that the USD as stable reserve is over from a position of strength, not weakness. And transitioning to a neutral reserve asset system, as this article will explore in detail, will help us on-shore critical supply chains (particularly with inflation sending a signal to producers concurrently). Regardless, Gromen’s central point remains: thinking the dollar system is a net benefit to the US and wanting to sanction Putin without self-injury are mutually exclusive positions, yet many seem to think this is somehow possible.

If the USD’s changing status sounds inconceivable, then consider the following. How can other countries, especially those with lukewarm relations with the US, rely on USD as a reserve currency if it is now clear those reserves can be seized at any moment? As China and Russia started moving away from the USD as reserve currency in the early ’10s after watching the US weaponize the USD against Iran, now the entire world is awake and will look for alternatives (in fact, central banks’ gold purchase have outpaced USTs by 8x since 2014). Second, pressure will mount on the entire global financial system from rising energy and commodity prices, and it’s likely we won’t be able to weather it. We thus find ourselves in a situation where the Fed may be forced to print more money to prop up the USD system into oncoming inflation, when they had intended to raise rates. So while our sanctions will undoubtedly hurt Russia, we’re also inflicting pain on ourselves. This would not be true if the USD were not the global reserve currency.

Americans now recognize relying on Russian oil and gas is not a good thing for the West, and yet we have not made the leap that buying solar and batteries from China is an even more perilous situation. We have plenty of oil and gas at home, but we have effectively zero ability to manufacture solar and storage. What would we do if China invaded Taiwan? Stop buying their solar panels? And where would we get semi-conductors? While a Taiwan invasion is hopefully just an illustrative example and not within the realm of actual possibilities, it has at the very least become clear that Russia and China are aligning against the West. With tensions escalating, it would be prudent to diversify away from China as a trading partner.

Thus, instead of just blindly perpetuating economic and monetary systems conceived decades ago, we should be asking what our aims are and how we can achieve them. Many of the more forward looking suite of policies in the tweet above are not possible with the USD continuing its reserve status. This piece will explain why this is the case and argue for restructuring the US and USD’s role in the world. (The practical steps needed to prepare — or even encourage — a multi-polar currency world, or a neutral world reserve currency like gold, are better left to thinkers like Gromen.) What those in the energy community need to focus on is making the US an energy juggernaut in all facets: deploying enormous amounts of wind and solar in resource rich areas, on-shoring solar and battery supply chains (including more friendly, regional trading partners), funding and removing red tape for SMRs to revamp our nuclear industry (please do not focus on large LWR), fracking like crazy and exporting LNG, etc. If such a restructuring is successful, we may just be able to solve our domestic problems — from wealth inequality to the opioid crisis. Before we can discuss why this is the case, we must first look to our history.

Hydrocarbon Man and The Petro-Industrial Complex

In the modern world, one institution rules them all: the US petro-industrial complex, rooted in the petrodollar system. This new order emerged out of the chaos of World War II; fossil fuels, particularly oil, are the lifeblood of that system. Moving from a paradigm wherein oil is the most important input in our energy systems to one where electricity produced by non-fossil fuel power plants reigns supreme is a radical shift. Nearly all else will reform around that shift, from geopolitics to culture to economics. But in order to effectively discuss a renewables-dependent order, we must first understand the oil-dependent past.

“Whatever the twists and turns in global politics, whatever the ebb of imperial power and the flow of national pride, one trend in the decades following World War II progressed in a straight and rapidly ascending line — the consumption of oil… Oil emerged triumphant, the undisputed King, a monarch garbed in a dazzling array of plastics… His reign was a time of confidence, of growth, of expansion, of astonishing economic performance… It was the Age of Hydrocarbon Man.”

— Daniel Yergin in The Prize

Oil was the lifeblood that all else flowed from. The feedstock for the US’s economic might was access to cheap oil and formed the foundation of US hegemony. As such, securing oil supply became the primary national security interest of the US and other Western countries, starting as early as the 1920s when WWI demonstrated how important oil would be in warfare (and later validated to an astonishing degree in the German Blitzkreig, which stopped short due to lack of fuel). Originally, the US controlled the global oil trade because the US was the largest producer of oil by far, with Standard Oil alone dominating 80% of global oil supply in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Over time, new oil sources threatened to dethrone the US’s production primacy, predominantly emerging from the Middle East, while concurrently the American appetite for oil began outstripping its own supply. This problem drove a strategic need for exploration and access abroad. Meanwhile, throughout the 1920s and 30s, oil was discovered in Saudi Arabia, Iran, and Iraq. Because the US and US-based companies were the dominant oil force in the world, these emerging producer nations had to rely on them for development. Only the large oil companies had the capital and expertise to get Middle Eastern oil out of the ground, so they received concessions from Middle Eastern governments often negotiated with the help of the western (US, UK, etc) governments. In exchange for royalties on oil extracted, the producing nations gave Western oil companies leases on their land.

These deals in the Middle East in the 40s and 50s created the foundation for the modern system in which we still operate. However, as the importance of Middle Eastern oil increased, the power of these emerging nations grew. Gradually, they began taking more and more of the profits generated and asserted greater control over their own industry, constantly threatening to nationalize production (which did happen). Eventually, OPEC consolidated and emerged as the largest producer of oil, and with it the US became the global distributor and protector of this system, not the major supplier as it had once been. What remains is an interconnected web of multi-national corporations and banks: big auto, defense, aviation, and oil and gas companies, as well as consolidated farming operations dependent on fertilizer and many more. It is hard to imagine a sector where this complex doesn’t grow roots; the petro-industrial complex is the very ground we stand on in the modern world.

The Petrodollar System

What emerged out of this was the US petrodollar system, a currency system that tied it all together. For a complete history on this, please read Lyn Alden’s magnificent Fraying of the Petrodollar System, this piece by Susan Su, or Alex Gladstein’s Uncovering the Hidden Costs of the Petrodollar. Because I cannot hope to do better, I will quote Alden directly here:

“With the petrodollar system, Saudi Arabia (and other countries in OPEC) sell their oil exclusively in dollars in exchange for US protection and cooperation. Even if France wants to buy oil from Saudi Arabia, for example, they do so in dollars. Any country that wants oil, needs to be able to get dollars to pay for it, either by earning them or exchanging their currency for them. So, non oil-producing countries also sell many of their exports in dollars, even though the dollar is completely fiat foreign paper, so that they can get dollars for which to buy oil from oil-producing countries. And, all of these countries store excess dollars as foreign-exchange reserves, which they mostly put into US Treasuries to earn some interest.

In return, the United States uses its unrivaled blue-water navy to protect global shipping lanes, and preserve the geopolitical status quo with military action or the threat thereof as needed. In addition, the United States basically has to run persistent trade deficits with the rest of the world, to get enough dollars out into the international system. Many of those dollars, however, get recycled into buying US Treasuries and stored as foreign-exchange reserves, meaning that a large portion of US federal deficits are financed by foreign governments compared to other developed nations that mostly rely on domestic financing. This article explains why foreign financing can feel great while it’s happening.

The petrodollar system is creative, because it was one of the few ways to make everyone in the world accept foreign paper for tangible goods and services. Oil producers get protection and order in exchange for pricing their oil in dollars and putting their reserves into Treasuries, and non-oil producers need oil, and thus need dollars so they can get that oil.

This leads to a disproportionate amount of global trade occurring in dollars relative to the size of the US economy, and in some ways, means that the dollar is backed by oil, without being explicitly pegged to oil at a defined ratio. The system gives the dollar a persistent global demand from around the world, while other fiat currencies are mostly just used internally in their own countries.

Even though the United States represented only about 11% of global trade and 24% of global GDP in early 2018, the dollar’s share of global economic activity was far higher at 40–60% depending on what metric you look at, and this gap represents its status as the global reserve currency, and the key currency for global energy pricing.”

This didn’t have to be the case. The oil trade actually saved the USD reserve status when Saudi Arabia agreed to sell its oil in dollars in 1974. Under Bretton Woods (from 1944–1971), the USD was backed by gold. But as US debt mounted, French gunships actually showed up on our shores demanding to exchange USD for gold. Nixon was forced to decline the request, effectively ending the Bretton Woods system and putting the USD in an extremely precarious situation. Thus, this agreement with Saudi Arabia (and soon, all of OPEC) maintained global demand for USD despite not being backed by anything, as oil was the most important commodity. The petrodollar was born.

While some say the above description of the petrodollar system has been supplanted by the eurodollar (dollars deposited in European banks), that doesn’t make it any less significant. The eurodollar argument is something like: US dollars and strength are now so ubiquitous (the de-facto plumbing of the global economy) that the oil trade is insignificant, thus a shift away from oil won’t negatively impact the US position. However, what’s missed here is that the petrodollar was an explicit quid pro quo: use USD and get protection. This explicit trade is not the case with the eurodollar. Furthermore, oil still constitutes a huge portion of global trade, providing consistent demand for USDs. And as we’ve seen in Russia’s case, the USD system and US aims are now coming into direct conflict, where that was never the case in the early days of the petrodollar system.

Now, the USD as reserve currency is backed only by the implicit belief that the US is the strongest country in the world and will intervene when things get out of whack. So while the belief in the USD is ultimately what matters, that belief was built on the backs of guns and oil. What’s worse, we backed it with guns because oil had major strategic significance for us, whereas today much of dollar-denominated trade does not. Why should we care if USD is used in trade between France and Russia? In the case of Russia, the answer seems to be that we can use the USD itself as a weapon. But should we? Putin’s invasion is indeed monstrous, but our reaction threatens to bring down the entire global financial system— you may find my even asking callous, but we must at the very least be aware of these trade-offs. Regardless, the more apparent it becomes that the US cannot police the world, and thus only weaponize the USD itself instead, the more the world will turn its back on the dollar.

As the US’s role in the global trade declines, its position becomes less central globally. Countries will increasingly move away from the system toward inter-regional currency trading pairs (e.g. EUR/RUB), and it is becoming clear that the US has limited recourse to stop it. Whether it’s China’s growing aggression towards Taiwan, the Russian invasion of Ukraine, or our fiasco in Afghanistan, the likelihood that countries feel any sort of explicit threat by the US anymore, or that the US would ever follow through on such threat, is rapidly receding. And whether or not you buy the petrodollar argument, the simple fact remains: it would be far more prudent for US leaders to start focusing on securing supply chains of national strategic significance than maintaining a system that used to do such, and does not any longer.

“Stagnation”: What the Hell Happened in 1973?

The problems with the USD do not stop at supply chains, and our energy problem is tightly intertwined with our domestic labor and wealth inequality problems. While the causal direction is murky, the correlation is clear: the US has faced an economic stagnation (or rather a “divergence”) since the early 1970s, wherein bankers and international corporations win and domestic blue collar workers lose. An important driver of all of this was that energy got expensive.

While some argue the computing revolution and birth of the internet prove we never “stagnated”, the fact remains that we have completely gutted the American middle class. If there was growth, it was not evenly distributed (it diverged between classes). For convenience, I will use stagnation as a term to reference this widening gap, but in the classic Thiel vs. Andreessen debate, I stand somewhere balanced between the two. And if we are to steel-man a causal direction for this phenomenon for the purpose of this article, it would look something like this:

Structural increase in global energy pricing → emergence of the petrodollar → Triffen Dilemma (structural need for trade deficits) → globalization of industrial base → domestic wealth inequality

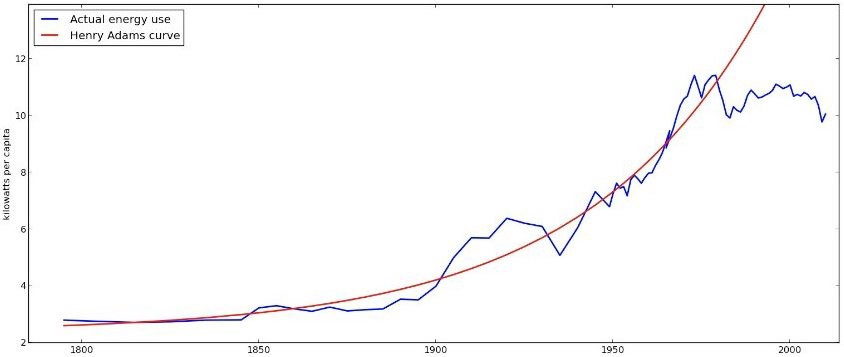

That is, as energy prices increased due to the growing demand from industrializing nations like Japan and Germany, the US sought cheap labor to blunt the effects of their not-so-cheap-anymore energy. The most fundamental inputs to the economy are labor, raw materials, and energy. Labor and energy can be exchanged to a degree but are certainly not identical. What the American Order established was that any nation protected by the Order could trade with any other country within the Order. Thus, if all nations had the same cost of energy and access to global markets, then the areas with cheap labor would be the cheapest places to produce goods, creating a countervailing deflationary force in the face of energy inflation. This ended the “Henry Adams Curve” in America, as we started offshoring energy-intensive industries, lowering our overall consumption.

While exporting our industrial base may not have been the intent of the petrodollar system, it is what happened. The phenomenon is described by the Triffen Dilemma which, in brief, establishes that in order to get enough dollars into global circulation, the US has to run structural trade deficits. That is, the only way to fund the system with enough dollars was for the US to buy more goods abroad than we sold. This made it very hard for domestic manufacturers to compete when selling abroad, as it effectively strengthens the US dollar against all other currencies, making our exports (our domestically made goods) more expensive against imports. Usually this would result in a weakening of the currency in question and a re-balancing for domestic manufacturing, but this is not so in the case of the USD because it is the global reserve currency (keeping demand for it elevated), as described in depth in Alden’s piece. The result of this was “globalization”, which is just a nicer term for exporting the US industrial base. US consumers gained access to cheap goods, but US workers saw job opportunities disappear and wages compress.

While it has led to an enormous increase in prosperity and quality of life globally (and we should be grateful), the USD reserve system seems to be at this point a root cause of America’s domestic woes. It may be silly to reduce the complexity of our current political situation to energy, ignoring class, race, culture, etc., but it is the case that economic growth can alleviate much of the social pressures we currently face. In a sense, 1973 was the year the economy became a zero sum game domestically. A lot of intricate narratives were spun to make this change politically palatable, but the result is the same: the rich got richer at the expense, to a certain extent, of everyone else in the US (but not abroad). Domestic labor lost, while the executive suites of multi-national corporations and banks that could manage the complexity of expanding supply chains, as well as international labor pools, won. So did the professional class of those that supported them, and anyone wealthy enough to own assets denoted in USD. While entrepreneurs could still find the “American Dream” of upward mobility, particularly in tech, all boats (domestic labor) certainly did not rise with that tide.

If we accept that expensive energy led to a structural need for cheap labor to counterbalance inflation, then the way out of our current dilemma is to find cheaper sources of energy. Oil and gas cannot provide this for us. We have reached fossil fuel’s theoretical thermodynamic efficiency limit, and, in a Malthusian sense, its role as a resource to spark growth. Said more simply, all our engines have reached max capacity. Luckily, the energy transition offers us not only cheaper energy inputs, but also new engines and more efficient, more productive outputs. It is not necessarily the case that we need to consume more energy and return to the Henry Adams curve, but the point remains that oil and gas as a driving force of economic prosperity has plateaued. What we can do is use insanely cheap energy to break this domestic “stagnation”.

Thus, another way of looking at our current economic stagnation is we have simply reached the global equilibrium between labor and thermodynamic conversion of oil into other productive uses, and we need something with a greater energy return on energy invested to reach the next cycle in generating humanity prosperity. It in turn makes sense that instead of money being backed by oil, the most important commodity in the world at the time, it will be backed by electricity, the most important commodity of the future. Humans have an uncanny ability to turn tragedy into opportunity: a prime example being that as we realized the whales we were hunting for whale oil were going extinct, we invented a superior, more sustainable light source in the form of kerosene. There is a way out; The Age of the Electron is arriving just in time.

An Antidote to The Triffen Dilemma: An ElectroDollar Paradigm

The US must rebuild its balance sheet. In a way, there are three resources that matter in this regard: secure access to raw materials, a robust industrial base to turn those materials into goods, and hard currency on the government balance sheet from the surplus of production to aid in financing strategic needs (as well as a robust military to defend what’s on the balance sheet). Post WWII, the US was dominant in all regards. We had the most gold, the biggest industrial base, endless access to food and raw materials, and the most powerful military in history. This is why Bretton Woods effectively used the US balance sheet (via the USD) to rebuild the world economy in the wake of the destruction of WWII. But with the world around us brought into modernity, the US can now step back in certain ways from its role and focus inwards.

While the American Order led to the largest boom in human flourishing the world has ever seen, our balance sheet is now effectively vaporized in all three dimensions. First, The Triffen Dilemma essentially moved our industrial base off-balance sheet into foreign countries. One way to understand this is in how many 100s of billions—if not trillions—of dollars of equipment financed by American corporations sit in countries like China. In a conflict, what if those factories are nationalized? We cannot just bring those assets back home — they’re stranded. At the same time, instead of focusing on securing access to raw materials, we’ve been focusing on securing shipping lanes of already produced goods from places like China. Luckily, the US has enormous amounts of resources at home or nearby, but we must focus again on extracting these resources as China has, for example, in their growing dominance of the African continent. We need secure access to materials for inputs as we onshore our industrial base. Lastly, what if foreigners want to stop holding their foreign reserves in USD and buying USTs? We would have no ability to finance anything at home, and would have to drastically reduce military spending and other entitlements. We need to unwind our over-levered 130% debt/GDP ratio and we need hard currency on our balance sheet to prepare for financing strategic future needs.

Resilience is about lessening dependence on foreign nations. Much in the same way foreign countries rely on the US for security, we in turn rely on them to finance the entire operation. Despite how powerful we appear, the US is essentially incapable of doing anything without others’ help. And in the face of de-globalization and escalating tensions abroad, it is imperative that the US is able to domesticate large swaths of our economy. People may view this as being a doomer, but that’s far from the point — we’re all expecting the music to keep playing, but it’s time to start asking, “what if it stops”? Luckily, cheap electricity, cryptocurrencies, and a gutted working class searching for a brighter future can converge into a new paradigm. We can move away from the eurodollar and petrodollar, embrace the electrodollar, and emerge a stronger and more resilient and unified nation in the process.

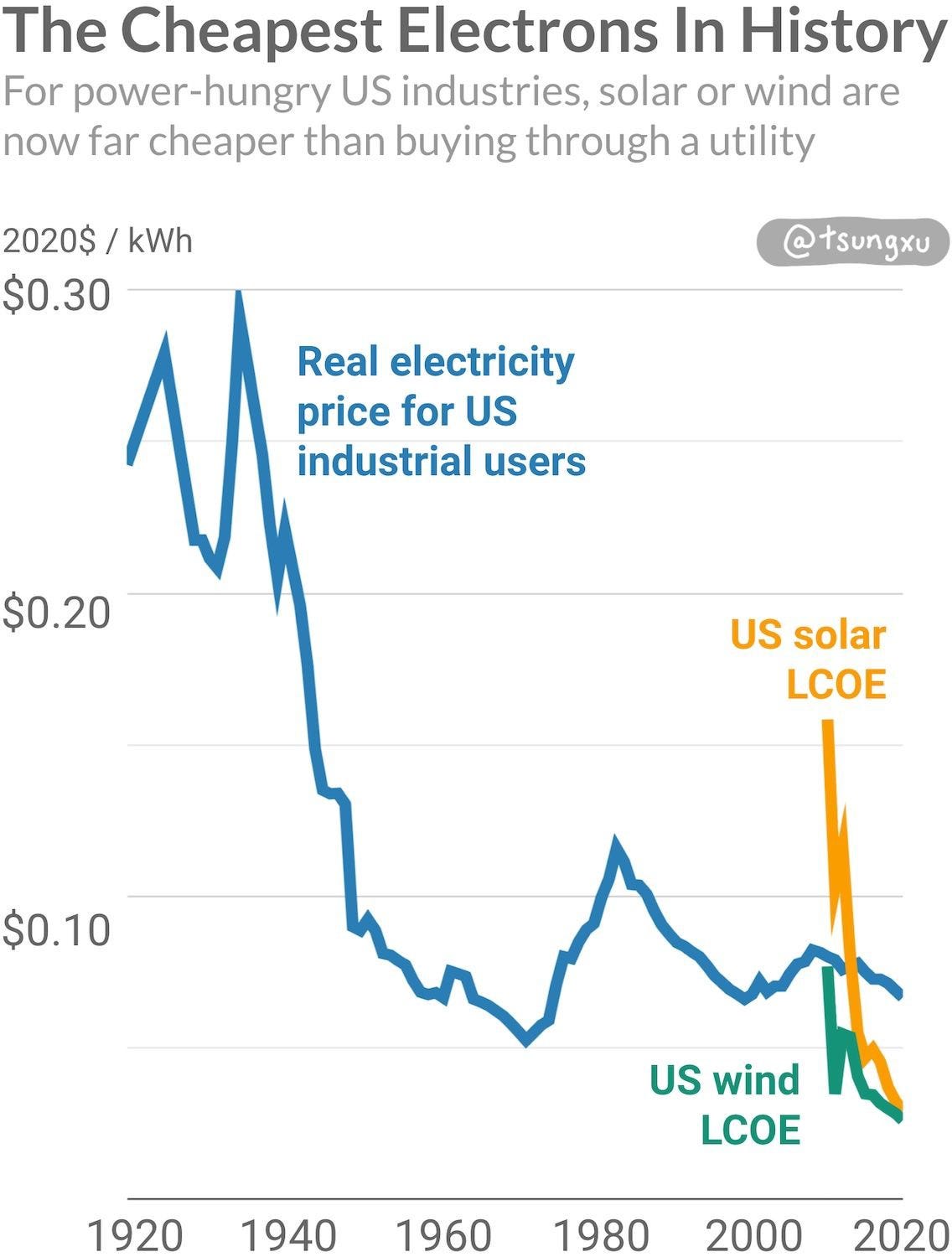

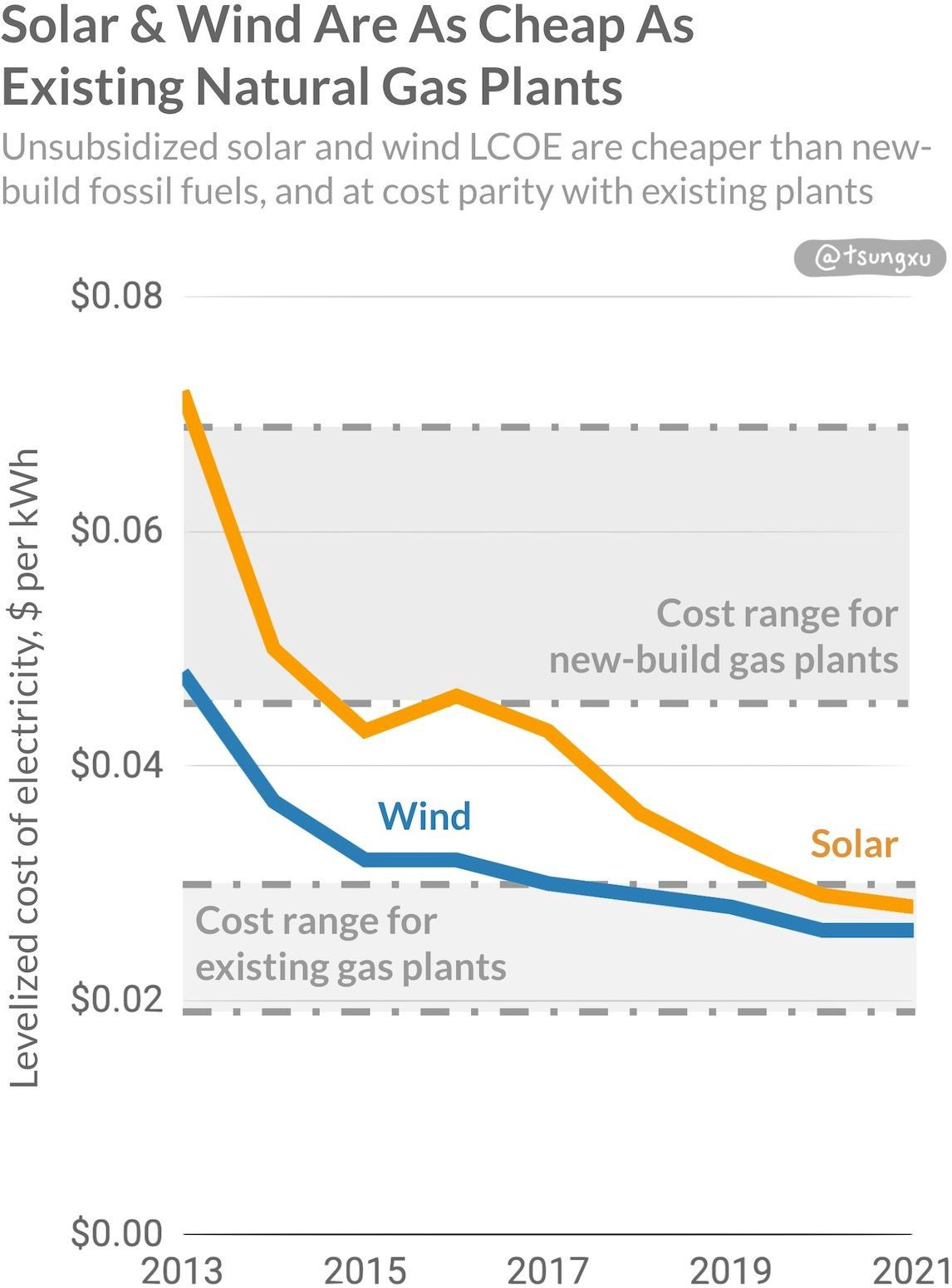

Energy is About to Get Insanely Cheap

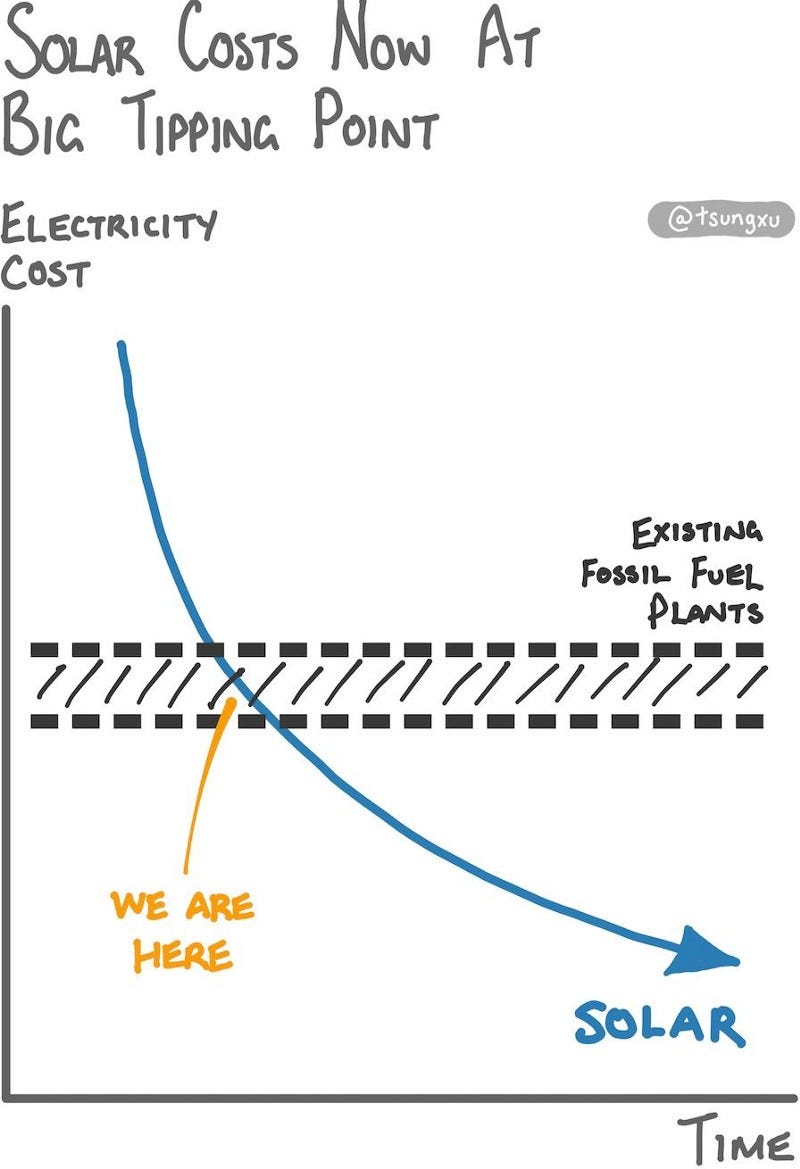

Unwinding the trade we made for cheap, globalized labor in the face of rising energy prices is simple: we need energy that is cheaper than fossil fuels (which clearly is not getting cheaper). Luckily, solar and wind are getting mind-blowingly cheap and are abundant in pockets of the country, but we need manufactured technologies to capture them. It would be great to include nuclear in the discussion, but the reality is it’s not cheap enough yet to compete with solar, wind, and gas in deregulated energy markets. For more on what we can do to kickstart our nuclear industry with SMRs listen here, but suffice to say that we need to be cutting red tape and funding early SMR projects immediately. Regardless of form, cheap energy breaks the “stagnation” cycle with a positive feedback loop that runs exactly counter to the negative one presented above:

Structural decrease in cost of energy production → deflationary effect on local energy prices → localization of industrial base → re-mergence of opportunities for domestic labor → electrodollar paradigm

Unfortunately, the current paradigm traps us between a rock and a hard place. First, cheap imports of clean energy are essentially financed by a fossil-fuel driven economic order as described in the petrodollar section of this piece. So as the petro-industrial complex and the USD’s reserve status wanes, our ability to secure cheap imports does too (we have already started to and will continue to see inflation). This means we must start to manufacture these technologies at home cheaply. However, the Triffen Dilemma concurrently makes it hard to manufacture anything at home (since domestic products are expensive compared to imports). So, while cheap imports of solar panels means the Triffen Dilemma helps create a deflationary effect on domestic energy prices and technologies and thus incentivizes local manufacturing of electricity-intensive industries, the Triffen Dilemma at the same time inhibits our ability to manufacture anything with the cheap energy. Cheap imports are a blessing and a curse, and at a certain point this tension will snap. So how do we break this cycle, while kickstarting a new one?

Only absurdly cheap energy at home can overcome the labor arbitrage we receive by manufacturing abroad. This is the silver lining in the Triffen Dilemma — some sort of weird Ouroboros when it comes to clean energy supply chains that goes as follows. We currently use the globalized supply chains to import cheap solar and storage. These resources provide cheap energy inputs and the infrastructure for its usage for 25 years or more. As the global economic order breaks down, we may see inflation in the price of imports. However, we’ll have already benefited from deployment, so we can then use really cheaply deployed energy from imported solar to domesticate manufacturing. Dirt cheap energy allows more expensive domestic labor to win out. We ought to make an effort to help this natural process along, as the risk is that we see inflation in solar and storage technologies before deploying all that much of them could prove to be catastrophic.

Thus, we need to find a way to concurrently avoid inflation in solar and storage through imports today, while incentivizing the manufacturing of them in the US for tomorrow. The problem with our current policy of only focusing on tax subsidies to spur deployment of panels and batteries is that it ignores this risk. We need to onshore solar and storage supply chains by any means necessary (among other strategic technologies like semi-conductors). One way to do this would be adding subsidies to manufacturing that would make them competitive with imports, then gradually ratchet up tariffs as we reduce the subsidies. Effectively, we’d be leveraging the USD’s reserve status (while it still exists) to spend heavily on on-shoring strategic industries like semiconductors and clean energy. The downside of this tactic would be that, despite creating actual domestic labor demand, spending can lead to further printing by the Fed and inflation, furthering the wealth inequality gap discussed prior. It may not be evenly distributed, which escalates domestic tensions.

Regardless, the irony of this entire dynamic is that the more solar, wind, and electric vehicles get deployed, the more the petro-industrial complex wanes and thus our ability to continue importing these technologies. It’s that very complex that is allowing for cheap imports in the first place. That is, we’re essentially financing imports of solar and batteries on the back of a fossil fuel-driven economic order, and at a certain point the trade will break. Thus, we must prepare for a time when the USD is no longer the global reserve currency and an end to the Triffen Dilemma, as we cannot indefinitely import solar panels on a trade deficit financed by the petro-industrial order. If we don’t start making these technologies, eventually we won’t be able to buy them. The hope is that, one way or another, the death gasps of one order may just create the foundations of the next.

Interlude: The Ethics of Money Production

It is easy to forget in our fiat-dominated world that money is produced, just like any other commodity. While it may seem that the USD lacks a cost of production, this is not the case (especially if we accept the assumption that the USD is backed by oil and gunships that run on oil). This idea is important to understand as we build a framework for the future of the global money system, so let us establish some basic principles.

In “The Ethics of Money Production” by Jorg Guido Hulsman, the author establishes plainly a few overlooked, but crucial ideas. The first is that:

“To be spontaneously adopted as a medium of exchange, a commodity must be desired for its nonmonetary services (for its own sake) and be marketable, that is, it must be widely bought and sold. The prices that are initially being paid for its nonmonetary services enable prospective buyers to estimate the future prices at which one can reasonably expect to resell it. The prices paid for its nonmonetary use are, so to speak, the empirical basis for its use in indirect exchange.”

In the case of the petrodollar, the “non-monetary service” provided by the US dollar was US military protection. As our ability to enforce global waterways recedes, so too will the global desire for this non-monetary service. However, this still does not explain the production of US dollars. The second idea that Jorg points out is on the nature of money production:

“How much money will be produced on the market? How many coins? The limits of mining and minting, and of all other monetary services are ultimately given through the preferences of the market participants. As in all other branches of industry, miners and minters will make additional investments and expand their production if, and only if, they believe that no better alternative is at hand. In practice this usually means that they will expand coin production if the expected monetary return on investments in mines and mint shops is at least as high as the monetary returns in shoe factories, bakeries, and so on.”

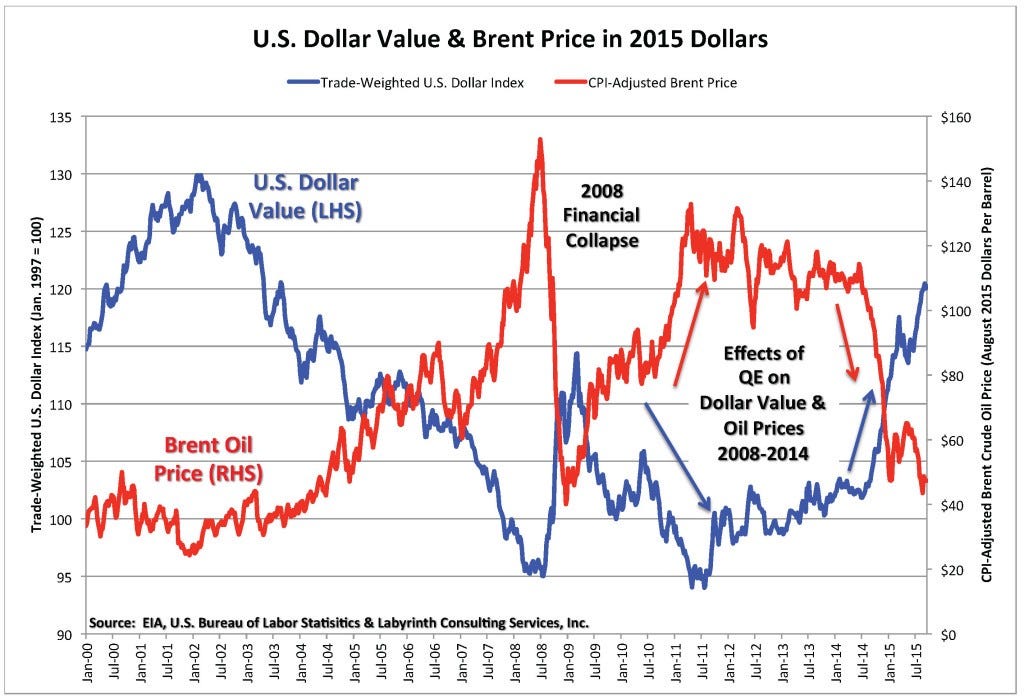

Put simply, there is no sense in using gold to invest in producing more gold when you can get higher returns elsewhere. But as monetary demand increases (through trade), it creates an incentive for minters and miners to invest in the production of money itself. The cost of producing money made sense in an era of gold and silver coinage, but how would that apply to petrodollars? An extension of Alden’s argument would be that US dollars were produced in relation to the production of oil. That is, the ebbs and flows of the oil trade and how much oil producers decided to invest in production dictated the amount of dollars needed to fund that system. In this sense, despite being a “fiat” system, US dollars from 1973 until 2008 have actually been produced in accordance with the dynamics of global energy markets.

Despite the focus of this piece being on bitcoin, this does introduce a slight wrinkle to the thesis. The jury is still out on whether or not it’s the right currency for this new electrodollar paradigm at scale, even if proof of work seems to have staying power for all the reasons soon to be described. In the “Ethics of Money Production”, it’s clear that the author believes that “ethical” money production is market-driven. Meaning, as demand for the currency increases (as it is used in trade), the price of that money will increase against other goods and commodities. Thus, miners and minters will receive a signal to mine and mint new money to maintain balance between the currency and the goods and commodities people trade with it.

Ironically, bitcoin’s supply was established by “fiat” by the creator, Satoshi Nakomoto. Only 21 million coins will ever exist. The argument for this is that any new production of money is theft against savers of that currency. This is a reasonable argument in the face of our current fiat system that is tyrannical in the other direction: when money can be printed at will, it is effectively wealth transfer from savers to producers. Particularly when is is the only currency in town, and its usage is enforced (militarily and societally). A fair point.

The counterpoint, however, is that fixed money supply introduces a new tyranny: the price of money will continue to rise against other goods and commodities, essentially turning savers into a landed aristocracy. It effectively says that savers do not need to reinvest their savings into the economy to continue receiving gains. Of course, there are passive ways to receive a return on savings in a sound economy. As long as savers have equal opportunity to participate in investing in the economy, it is not moral to insulate them from risk. We all must take risks and we all should participate. Life is tough; nothing is certain. And furthermore, as long as there are alternative currencies (unlike in the case of the USD), savers can always switch to others if it is being overproduced. Said another way, money should have supply/demand dynamics in producing the money itself, and it should also compete with other monies.

This is not an actionable perspective and is a bit of a moot point, as bitcoin functions in this paradigm for now. Of course, in a truly free-money system (where the currencies themselves compete), the only way for the price of bitcoin to drop is through decreased demand. So if bitcoin gets too expensive against other goods, and there is no way to reduce the price of that through new supply, market participants may freely look for other mediums of exchange. As long as bitcoin has to compete against other monies, there is nothing immoral about its pro-saver bend. New cryptocurrencies will continue to be freely made and used, and that’s a good thing.

The Electrodollar: Bitcoin and the Grid

Unlike the petrodollar, the relationship between energy and money in bitcoin is explicit from day one. What is key to understand is that in the Age of the Electron, end use of energy will convert primarily to electricity away from fossil fuel-based combustion as an input. Concurrently, we see emerging a powerful property of bitcoin mining that it creates a clearing price on what we actually consider productive use of electricity. This in turn would incentivize only real GDP growth, something that we seem to be losing track of in the petrodollar construct. Meanwhile, miners are incentivized to mine using the cheapest power, which is already renewables in many parts of the world. The electrodollar thus offers us a potential way out of the stagnation inherent in the petrodollar system and a new institutional order that can better support increased productive capacity while ensuring our decarbonization efforts succeed. Climate-concerned detractors of bitcoin need to take note of the fact that, by railing on bitcoin in support of the USD, they are by extension supporting the petro-industrial complex. So let us just look at what’s happening with bitcoin mining today with an open mind.

While a return to “hard money” via bitcoin is an attractive idea in the context of our fiat excesses, the most interesting property of bitcoin is that it creates an explicit signal to what “productive” means for power consumption. Recall Hulsman’s words quoted above:

“As in all other branches of industry, miners and minters will make additional investments and expand their production if, and only if… the expected monetary return on investments in mines and mint shops is at least as high as the monetary returns in shoe factories, bakeries, and so on.”

While many complain about bitcoin’s energy intensity, it is actually its greatest feature. Primarily in the security it brings the network, but secondarily in the incentive structure it creates. If you can make more money using power to mine the currency that enables trade than you can actually producing a good to trade for the currency, then you probably shouldn’t be using power to produce whatever that good is. That is, bitcoin mining acts as a filter by disincentivizing economic activity that will not lead to actual growth in productive surplus. This is unlike the fiat currencies we have today that, through cheap debt and targeting 2% annual inflation, drive us towards spending, mindless consumption, and creating companies that are oblivious to true value creation.

This is not just theoretical, as we can see this play out in real-time today (for the best analysis of this phenomenon, please read this excellent piece). It does come with some caveats, however. Bitcoin miners are indeed flocking to the cheapest sources of power (and thus best places to mine) around the world, and manufacturers are not far behind. In the US, this is primarily Texas due to a wealth of cheap domestic wind, solar, and natural gas production (and yes, areas like Kentucky are using bitcoin to try to prop up coal, but bitcoin is not going to save coal so it is merely a short term concern). But, the dynamic of the price of bitcoin setting the clearing price for productive output described above is likely far off. Still, in places like Texas, we can get a glimpse into what the future holds.

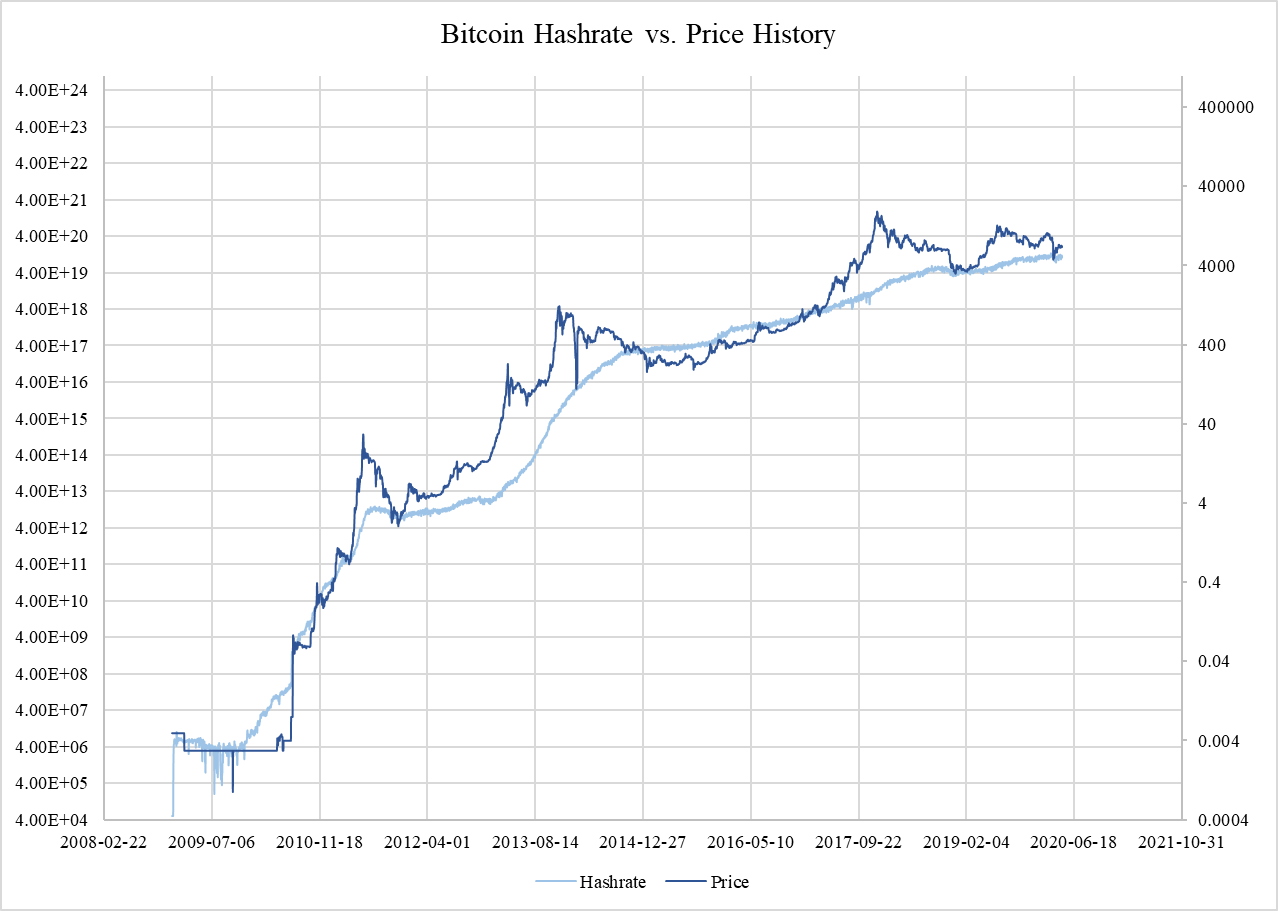

First, the bad news. At the current price for Bitcoin of ~$40,000, the hashrate of the network, and using a brand new ASIC miner, the break even cost to mining bitcoin is roughly $280/mwh. For older, less efficient miners, it can be as low as $100/mwh. Meanwhile, the average price of power in places like Texas is as low as $30/mwh. This means mining is still profitable well above the average cost of power, and thus could sap up supply and inflate prices for other productive uses (however, many industrial processes are still profitable well above $280/mwh). This is where the overblown concerns that bitcoin is an energy hog and will push costs for “productive” uses comes from.

Now, the good news. First, hashrate (the amount of computing power being used on a cryptocurrency network to verify transactions) has consistently increased as prices increase. A higher price per bitcoin incentivizes more miners to enter the network, making each miner require more energy to get a reward from the increased competition (more tries at solving the puzzle), compressing the price at which it’s profitable to mine. If bitcoin is to become a widely used currency, eventually the price must stabilize, and with it the hashrate will also, such that there is a reasonable (much lower than today) spread between the reward received for mining bitcoin and the marginal cost to produce it. Second, miners in Texas and elsewhere are already proving to be rational economic actors and are shutting down mining as the price of power exceeds their marginal cost to mine. Third, the demand for power from bitcoin mining is driving the build out of new power plants, which will drive power prices for these new builds lower. When you put these three things together, you see that bitcoin mines could lead to net new cheap capacity and a reduction in average prices of power at scale. This is because when power supply is constrained, each mine shuts off at its marginal cost to produce, freeing up capacity built for mining for other productive uses.

An interesting fact emerges out of these real phenomena: assuming in the Age of Electron that all processes are run on electricity, bitcoin creates the strike price determining what is actually valuable to the economy. Today, bitcoin mining’s profits are the spread between the price of power and its break even cost to produce, say $30/mwh to $280/mwh, so you make $250/mwh of power consumed (and need to pay off the cost of your miners). That means, you are better off producing any good whose spread is greater. As bitcoins profit margins compress, this spread will be smaller too. Said another way, you will be more profitable creating money (mining bitcoin) than you would creating and selling goods for said money. Only those goods that can be traded for more bitcoin than the equivalent value of the electricity needed to produce them will be produced. As Hulsman points out, this has been a property of money for thousands of years that we have forgotten only over the last thirty. With the caveat pointed out above that no new supply of bitcoin is actually being “produced”, a potential problem way down the road.

One popular concern is a fear that bitcoin will use up all of the cheap power, but the truth is quite the contrary: the fact that bitcoin is the floor for economic activity creates an incentive to build power plants as cheaply as possible, which benefits all productive uses of power that create goods at prices above the floor. The marginal cost to produce bitcoin will settle at the lowest possible price to generate electricity, and only enough mines needed to secure the network will be built. Because hashrate and bitcoin’s price are correlated, there will be a plateau of new mines built, leaving lots of excess capacity for cheap power to go towards other uses. If bitcoin truly incentivizes net new generation capacity on the grid, then its presence will lead to far lower average energy prices than in networks without bitcoin mines. This requires of course letting these incentives play out: if mines rush in and inflate power prices, it will create a signal to build more capacity.

Bitcoin mines thus act as a stabilizing force for power grids. Ultimately, this means that industrial loads will follow the bitcoin mines, and an equilibrium will be reached between creating money (mining bitcoin) and creating goods, the long-standing property of money and the economy that we have diverged from only recently. And because electricity is so expensive to transmit, we will move production of goods to where power is cheapest, too — not just production of bitcoin. This is a meaningful difference from the petro-industrial complex, where we went to where oil was cheapest, extracted it, and then sent it to where we created goods. We could do this because shipping oil was comparatively cheap. In cheap energy networks, bitcoin mines will move in first and industrial centers will follow not be far behind. That is, cheap labor pools may not have access to cheap power, disrupting the globalized dynamic that exists today.

Of course as alluded to above, bitcoin mining is not purely driven by price. Hashrate cannot increase infinitely because it requires ASICs, which require manufacturing capability of microprocessors. When looked at it this way, bitcoin mining is even more potent of a currency: it finds the equilibrium between manufacturing more microprocessors (power input) and devoting microprocessors to other productive tasks (server load). In a digital world, bitcoin creates an equilibrium on productive capacity between electricity generation capacity and server capacity. If we’re lucky, it may mean a future in which fewer social media and adtech companies use computationally expensive processes to sell cheap goods no one actually needs.

Of course, because we are so early on in bitcoin, maybe the electrodollar does not wind up tied to bitcoin. But the dynamic remains the same. Are miners rushing to cheap spots on the power grid so different than so many laborers and entrepreneurs flocking to San Francisco in 1849 for the gold rush or to Texas for oil production in the late 1800’s, rather than using their labor and talents to actually make something that could be traded for gold or required oil to produce? Like then, the “bitcoin mining rush” won’t always be the case. As the network matures and price escalates, reducing the upside potential of early adopters and yet inviting more miners in because of the high reward, the marginal cost of production of a bitcoin and the price of bitcoin will converge. This happens with all commodities and there is nothing that suggests bitcoin would be any different. On the grid, this implies the strike price at which miners shut down will decline substantially as well. Said another way, mining will only become profitable when electricity is cheapest, and will not block other, more productive uses of power instead — bitcoin will only be mined when the value of a bitcoin outstrips the cost to produce it (energy), which will get lower over time.

Ironically, climate-focused detractors of bitcoin often argue in favor of the USD and thus in support of the petro-industrial complex. Sure, you could conceivably shift USD to be renewables focused, but it would be naive to write-off the decades of institutional inertia preventing this. Meanwhile, solar and wind are the cheapest sources of power we now have, and that’s exactly where bitcoin mines are headed. As perfectly summarized by Michael McNamara from Lancium in a recent email exchange, solar prices in Texas are headed towards $10/mwh (maybe even $5), and mining revenues will be driven down to $30/mwh over time (down from ~$250mwh today). Bitcoin and solar thus share an inseparable fate, creating a strategic need for the US to focus on not only deploying solar, but manufacturing it as well. And that’s exactly what we’re starting to see play out in places like Texas.

An Industrial Renaissance

The dynamics of electricity generation described above, wherein it is cheaper to move production to power than it is to move power to production, will (luckily) lead to the rapid re-onshoring of supply chains, without us doing much else at all. If 1973 was the year that energy prices irreversibly increased, forcing industrialized nations to start globalizing in order to find cheap labor to replace the access to cheap oil they had for decades prior, then 2021 is the year that this changed. Electricity production, due to solar, wind, and natural gas, is now so cheap that choosing to manufacture where the cheap energy is rather than where the cheap labor is is starting to pencil out.

This inherently means that the domestication of supply chains to areas where cheap electricity is abundant is a feature of the energy transition and the Age of the Electron. Transmission of electricity, while important, gets outrageously expensive even shipping it 1,000 miles. We can somewhat reasonably send Panhandle wind to California in the future, but certainly not to Taiwan. This dynamic is very different compared to the global oil trade, where production of Saudi oil ($2/barrel) plus the costs of shipping it to end users in the US is still radically cheaper than producing in places like Texas ($40/barrel) right next to end users. Said simply, building high voltage power lines from here to Saudi Arabia is inconceivable compared to the ease of using oil supertankers.

Applied to the US, cheap electricity generated by solar, wind, and natural gas is enough to overwhelm even the powerful dynamics behind the Triffen Dilemma. On cue, something beautiful is emerging in West Texas: an industrial renaissance that not even the inertia behind the petro-industrial complex can stop. Why are semi-conductor and electric vehicle manufacturers alike suddenly flocking to Texas? In electricity intensive manufacturing processes, the cheap energy inputs and lack of shipping costs can actually win out over the cheap labor that globalization provides access to. It seems we are starting to wake up to the importance of this to some degree, but we are likely 15–20 years behind our rivals in starting the on-shoring process. And we’ve yet to fully confront the massive threat of where we get the electricity generators of the future.

Domestic Battery and Solar Manufacturing is a National Security Issue

China is the Standard Oil of solar panels and batteries, two of the most important technologies in the Age of the Electron. Despite the fact that the Lithium-Ion battery was invented by an American (still working at UT-Austin) and solar PV was invented at Bell Labs, we do not make any of these homegrown inventions in the US. That is a huge problem and was certainly not inevitable. In much the same way we developed a strategic political focus on the Middle East because of access to oil, we need to start focusing on the energy supply chains of the future. Today, US leaders have no such focus and are letting an emerging China dominate where it matters — namely solar PV and battery production (although that is luckily starting to change, it’s not yet the mainstream, bipartisan view that it must be). While we benefit from an abundance of cheap natural gas and our aging manufacturing giants like GE show prowess in wind turbine manufacturing, we are embarrassingly lacking in two of the most critical technologies of the future. We must make them on US soil, or at least on those friendlier than China’s.

If solar, wind, and natural gas are the power sources of the Age of Electron, then batteries are the motor. Batteries are to electricity what the internal combustion engine was to oil, or the steam engine was to coal. Of course, batteries are not a motor whatsoever, but they are the fundamental technology that enable the motor, so we can treat them the same. Compared to the internal combustion engine, batteries benefit from economies of scale despite being small and modular. Because they are storing work already done from, say, a Natural Gas Combined Cycle power plant at 67% thermodynamic efficiency, and with a round-trip efficiency of 90% on their own, they are exceptionally more efficient than a 35% efficient traditional combustion engine sitting in a car. Batteries break us out of the Malthusian stagnation that combustion processes alone lock us into, and the Age of the Electron wouldn’t happen without them.

Furthermore, solar panels are marked by their remarkable ability to provide resilience to a centralized energy system. In fact, they represent the only mechanism we have to independently produce energy in a distributed manner. Natural gas, propane heaters, diesel, gasoline, and more all require extensive distribution networks, unless you happen to have an oil derrick and refinery in your back yard. Despite only producing when the sun is out, once you own the panels, solar will generate power wherever it is for 25+ years. And paired with a standalone or electric vehicle battery, they can provide power at night (the Ford F-150 for 3+ days). We are still collectively underestimating how transformational a technology rooftop solar is in scaling human flourishing. As developing countries leapfrogged landlines for mobile, so too will they leapfrog centralized grids for solar and storage driven decentralized ones.

And yet, China manufactures 70%+ of solar panels and battery storage, including the raw materials supply chains leading up to the manufacturing process. If we’re to rely on these resources, that needs to change. Projecting into the future China’s dominance of clean energy supply chains in both solar panel and battery manufacturing — which mirrors that of Standard Oil and the US’s early dominance in oil the late 1800’s — coupled with the US’s waning industrial might and the fraying of the US Dollar as the reserve currency spell trouble for the US. However, it is not too late for us to act — we’ve already found rich lithium deposits in friendly neighborhoods like Chile, Australia, or even our own backyard.

Not only is our access to critical technologies for our own needs in jeopardy, but our ability to provide values to others is also at risk. Developing nations will turn to Chinese manufacturers of these technologies, not to GE for goods or to Exxon to develop oil fields, as they did in the past. Batteries and solar, while critical, are only one example of the myriad ways in which the US offshoring manufacturing is a terrible strategy. The same could be true of semiconductors, steel, aluminum, pharmaceuticals, medical devices, or literally any basic necessities and infrastructure. Aside from our navy, which cannot be financed as the petro-industrial complex unwinds, what will future trading partners actually need us for?

So if there is one thing to take away from this piece, it is this: the structure of the USD as reserve currency prevents us from making anything at home. There is no keeping the system as is, and also bringing home manufacturing; you are for, or against. We must transition to a neutral reserve asset world, and prepare ourselves for the inevitable decline of the petro-industrial complex. The dynamics of the Age of the Electron are drastically different than those of the Hydrocarbon Era, and our current position as global hegemon does not necessarily help us step into this new environment, precisely because it carries with us the burdens of the past, which no longer help us. There are plenty of advantages to exploit, if only we could stop the infighting and look to the future. Of them, access to cheap electricity is the single most important weapon we have, a deflationary force in an inflationary world.

Conclusion

This is not an energy transition, it is an energy revolution. Institutions of old will eventually break, and they will not go quietly into the night. This fact demands a certain vigilance in the approach to building new ones; the incumbents are not our friends, despite speaking as if they are, and are not to be trusted. Because when push comes to shove, the incentive structures are what they are, and the petro-industrial complex wishes only to perpetuate itself. And its perpetuation now exists in conflict with our strategic aims. Going forward, we must rely on our own minds and think from first principles, for that will be the only way to know what is what and carve a path into a more optimistic future. We cannot rely on what worked in the past.

So above all, this is a call to action. It is my personal belief that whether it’s criminal justice reform or converting to clean energy, Americans actually agree on 70% of major issues (when described in certain ways). But it’s in the interest of incumbent power structures to keep us divided by fanning the flames of our domestic culture war in order to distract us from their attempts to perpetuate a system that’s now clearly failing us, and serving only them. American corporate interests have diverged from those of its people, and US national security over the next decade is undermined by the interests of our very own petro-industrial complex. This is also true of the USD’s status as the global reserve currency, as it actively prevents the onshoring of vital technologies. But what can we actually do about it?

Here’s my proposal:

We need to build more solar and wind, frack like crazy, and fund early deployments of SMRs (Small Modular nuclear Reactors). We need to on-shore manufacturing semi-conductors, solar, battery storage, medical devices, and any other strategic asset. And in order to do all that, we need to transition the world to a neutral reserve currency, away from the USD. We need to turn our attention back to gold on our balance sheet, and we need to embrace bitcoin. We should tax bitcoin miners in bitcoin to slyly rebuild our balance sheet (instead of weakening the USD by central banks buying these assets on open markets). We need to de-lever our food productions’ reliance on fossil fuels and we need to build strategic alliances with countries who actually have something to offer us, like vital raw materials. We need to reinvigorate domestic labor. And we need to stop squabbling amongst each other, which our enemies abroad love.

The world is increasingly becoming an unfriendly place for us, and it’s in our best interest to recognize this and start working together, domestically. In the energy sector, infighting between people who love to “dunk on the greens”, or those who see O&G companies as the devil helps the incumbents. It’s exactly what they want. So it doesn’t matter how we get it done, or if it’s Democrats or Republicans proposing some new measure, or both, or even some new party. It doesn’t matter if it’s the government or the private sector leading the charge. It doesn’t matter who voted for who in the past or if their beliefs are different. What matters is that we can coexist respectfully, without wanting to destroy each other (and ourselves in the process). What matters is earnestly working to make ourselves better, our communities better, and our country better, and acting in good faith trying to solve problems. And building new systems that level the playing field for average Americans, not tip the scales towards multi-national corporations and banks, and a detached elite ruling class. We have everything we need to win, but our greatest threat is ourselves. We just need more unabashed Patriots. Americans must unite, before it’s too late. And we will, because we must.

My readings seem to indicate that the planet has a huge problem with the lack of raw materials to make the transition over to solar, EV, and wind generation. It's all pie in the sky if we can't get the rare earth minerals and copper out of the ground fast enough.

Very thoughtful and insightful article. I was expecting cringe talk about climate change, but it was refreshing not have to deal with that. However. The introduction of taxing BTC provided no further explanation why anyone needs to be taxed at all - if we are returning to sound money (and dialing back the clock of the FED / IRS acts of 1912). Why disincentivize Bitcoin mining? That makes no sense. Otherwise, I would have distributed this article far and wide.